COHESIFY partner meeting in Warsaw

December 14, 2016

COHESIFY partner organises communication event in Madrid

January 19, 2017On 16 November 2016, General Affairs Council concluded that the renewal of Cohesion policy needs to consider “the introduction of differentiation into the implementation of the ESI Funds programmes based on objective criteria and positive incentives for programmes”.

For the first time since 1988, serious thought is being given to reforming fundamentally a key principle of Cohesion policy – shared management of the Funds between the European Commission and Member States. While any differentiation is anathema to some Member States, for others it may be the price of their continued support for the policy.

The origins of the dilemma facing Cohesion policy go back almost exactly 18 years. In December 1998, the European Parliament’s Budgetary Control Committee voted against discharge of the EU budget, triggering a sequence of events that would end with the resignation of the European Commission under President Santer. The new Commission was compelled to take a much tougher approach to combating fraud and controlling EU expenditure.

The implications for Cohesion policy were dramatic. In the course of the early 2000s, the closer monitoring of the regularity of EU spending found ‘unacceptably high’ error rates of up to 12% in spending under Structural and Cohesion Funds. Under pressure from the European Court of Auditors (ECA) and European Parliament, progressively stricter requirements for financial management and control were introduced – labelled an ‘audit explosion’ – with major organizational, strategic and operational consequences.

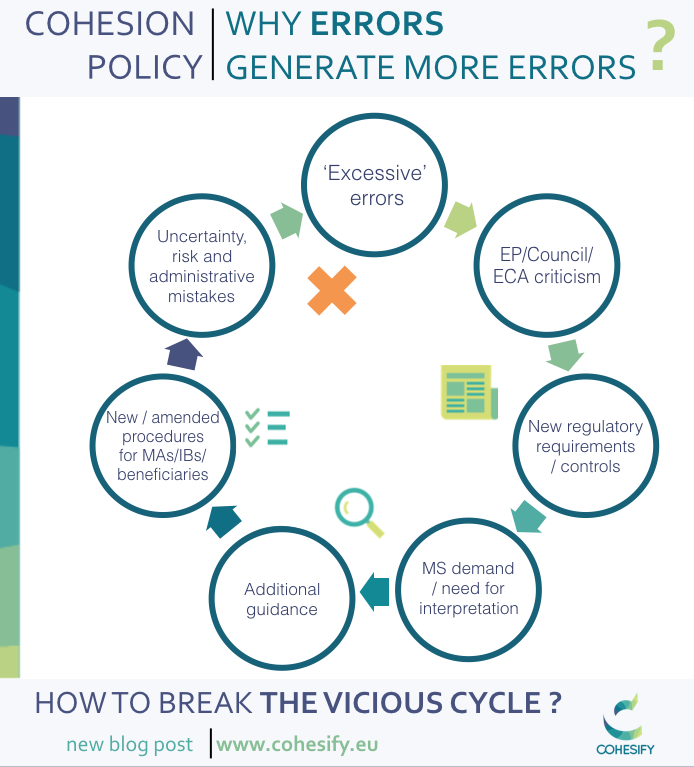

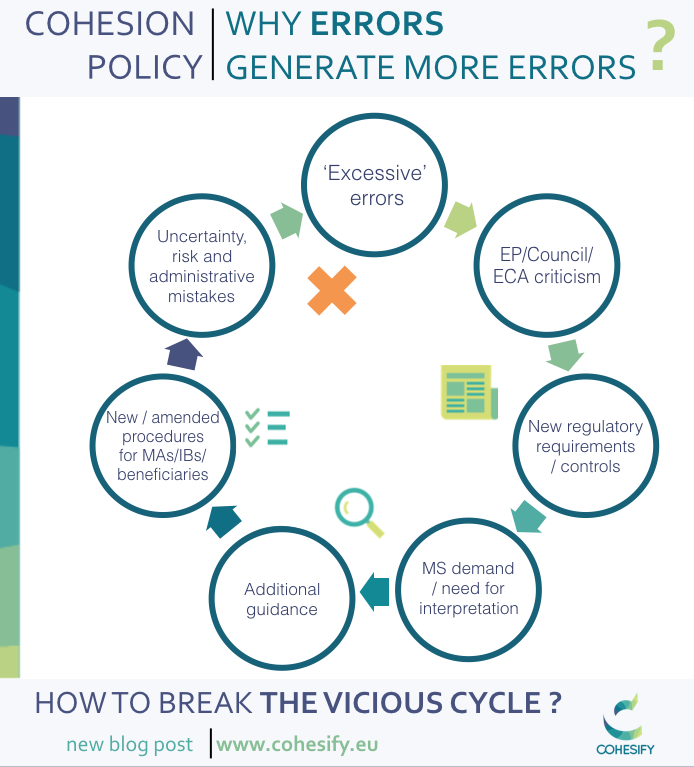

Over successive programme periods, the dynamic of Cohesion policy has been driven by the imperatives of compliance and multiple layers of audit in an effort to reduce the error rate. Indeed, as illustrated below, the policy has become locked into a vicious cycle, driven by the annual reporting on the error rate by the Commission and ECA and colouring perception of the policy by the Parliament and the Council. Political criticism of ‘excessive’ errors has generated new regulatory requirements; once introduced, Member State authorities expect these to be interpreted by the Commission to reduce the likelihood of audit challenge. New rules and guidance then require Managing Authorities (MAs), Intermediate Bodies (IBs) and beneficiaries to adapt administrative processes and procedures. Inevitably, change introduces uncertainty, risk and scope for administrative mistakes, which, if picked up through audit, may be classed as errors. And so the cycle continues.

Complexity and the error rate cycle

This is a universal problem affecting all Member States, and the creation of a High Level Group on Simplification is a welcome initiative to consider how the administrative requirements of the Funds could be rationalised. Steps like simplified cost options, greater proportionality and standardization of national verifications all have a role to play.

However, the problem of administrative complexity has a distinctive dimension in richer countries and regions receiving smaller amounts of EU funding. Here, the proportion of ESIF may be very small compared to domestic expenditure on economic development, and EU rules and procedures often differ from national ones.

This is a universal problem affecting all Member States, and the creation of a High Level Group on Simplification is a welcome initiative to consider how the administrative requirements of the Funds could be rationalised. Steps like simplified cost options, greater proportionality and standardization of national verifications all have a role to play.

However, the problem of administrative complexity has a distinctive dimension in richer countries and regions receiving smaller amounts of EU funding. Here, the proportion of ESIF may be very small compared to domestic expenditure on economic development, and EU rules and procedures often differ from national ones.

This is a universal problem affecting all Member States, and the creation of a High Level Group on Simplification is a welcome initiative to consider how the administrative requirements of the Funds could be rationalised. Steps like simplified cost options, greater proportionality and standardization of national verifications all have a role to play.

However, the problem of administrative complexity has a distinctive dimension in richer countries and regions receiving smaller amounts of EU funding. Here, the proportion of ESIF may be very small compared to domestic expenditure on economic development, and EU rules and procedures often differ from national ones.

This is a universal problem affecting all Member States, and the creation of a High Level Group on Simplification is a welcome initiative to consider how the administrative requirements of the Funds could be rationalised. Steps like simplified cost options, greater proportionality and standardization of national verifications all have a role to play.

However, the problem of administrative complexity has a distinctive dimension in richer countries and regions receiving smaller amounts of EU funding. Here, the proportion of ESIF may be very small compared to domestic expenditure on economic development, and EU rules and procedures often differ from national ones. With a relatively small proportion of staff involved in ESIF administration in departments/agencies responsible for MA and IB functions, there is a heightened risk of differences between EU and domestic rules in (for example) procurement practices, eligibility rules and other administrative processes, resulting in errors. In this context, the growing complexity of financial management and control is contributing to disproportionately high administrative workloads. More corrosively, it is causing a loss of trust and confidence in the policy, to the extent that some IBs and beneficiaries are deciding to avoid involvement in ESIF where there are alternative domestic funding opportunities. Efforts to address these problems through regulatory provisions for proportionality have, so far, been marginal and made little difference.

Not surprisingly, the need for ‘differentiation’ in the management of Cohesion policy is now a central topic in the debate on reforming the policy after 2020. The question is whether and how a differentiated approach could be designed that moves away from the one-size-fits-all model of shared management and which recognises that different models are appropriate for different contexts.

A starting point is to consider the principles that would need to guide a differentiated approach – or the minimum requirements that the Commission can justifiably expect from all Member States and programmes. These would certainly include: (a) coherence with Cohesion policy objectives and wider EU economic governance and industrial policies; (b) assurance on the regularity and legality of spending; (c) evidence on the performance of EU funding and the outcomes achieved; and (d) a commitment to the principles of partnership.

Based on these principles, it might be possible to conceive a new model of devolved management - as opposed to shared management - based on partnership and cooperation, which would be inspired by the current ‘direct budget support’ approach. This might have the following elements.

First, Member States would elaborate national strategies for territorial/regional development and cohesion (or demonstrate that there is a domestic strategy in place) and negotiate these with the Commission to ensure they meet regulatory requirements. The Commission would clearly want to be assured that pre-conditions (conditionalities?) relating to sound financial management, performance and partnership are met.

Second, Member States would implement the strategies – in terms of management, monitoring and controls – according to national rules and administrative arrangements without the need for approved OPs. Relevant EU rules on State aids, public procurement, the internal market and environmental protection would need to be fulfilled.

Third, Member States would commit to regular reporting to the Commission and Council on the progress and performance of their use of EU funding. Financial payments would be approved by the Commission based on the demonstrated achievement of agreed outputs or results. Audit would be the responsibility of national audit services; verification of the work of these services would be undertaken by a single or limited number of system audits by the Commission audit or ECA.

Lastly, the Commission would have the scope to implement Community initiatives to respond to specific challenges or opportunities. It would also facilitate coordination of the exchange of experience across Member States within the framework of the open method of coordination.

A key issue, of course, is which criteria should be used to justify the use of devolved management in some Member States. A recent study exploring new ideas for post-2020 Cohesion policy has presented a range of options. Some are related to the scale or proportion of EU funding or the share of EU co-financing (essentially measures of EU funding ‘at risk’). Others relate to measures of implementation such as the level of absorption. And quality of government might also be considered, given the evidence for its influence on financial compliance and the increasing recognition of the importance of administrative capacity for sound management of ESIF.

Introducing differentiation into the management of Cohesion policy will not be easy and might well cause unintended consequences. However, it is an idea whose time has come and deserves to be part of the debate on post-2020 reform of the policy.

Professor John Bachtler and Dr Carlos Mendez European Policies Research Centre, University of Strathclyde